1. Famous Chinese Paintings

Famous Chinese Paintings was a bimonthly periodical published in Shanghai by the Yousheng Book Company (1904-1943), and distributed in a dozen Chinese cities. The first issue came out in 1908, and 40 issues were published. The first series included 22 issues. They were very successful and repeatedly reprinted in the 1910s and 1920s. A large two-volume version of the publication, including many of the previously published prints, concluded the series in 1930. The format of the publication may have been inspired by a similar periodical, Shina meiga shu (Collection of famous Chinese paintings), which started publication in Japan in 1908, the main difference being that the latter periodical reflected Japanese tastes and collecting practices1.

|

| Distribution points of Famous Chinese Paintings : Tianjin, Nanjing, Suzhou, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Yangzhou, Mukden, Zhenjiang, Nanchang, Hankou, Chengdu |

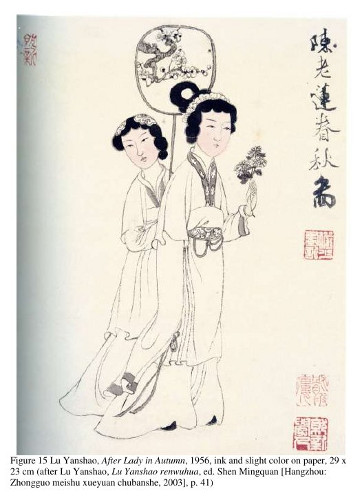

In the postface published in the fourth issue of Famous Chinese Paintings, Zhang Jia, its editor, mentions that the cultivation of an “esteem of beauty”, which he had witnessed in Japan the year before, is essential in the process of "political acculturation" of the people, and art publications could make a significant contribution in this respect. Such publications also provided inspiration for artists, as the traditionalist painter Lu Yanshao (1909-1993), while still in middle school, began his study of Chinese traditional painting by copying prints from Famous Chinese Paintings2, and continued using them for inspiration later in his life, as shown below.

|

|

| Chen Hongshou (1598-1652) (detail of 03_07) | From reference 2, p.90 |

The printing history of the periodical, given in the table below, shows that some issues were more successful than others, and that the periodicity was bimonthly only in the beginning. Issues 19 to 22 were published on a yearly basis.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Issue 13 had its 8th printing in June 1919 and 9th printing in August 1921. Issue 15 had its 5th printing in March 1919 and its 6th in April 1921. Issue 19 was first published in November 1916, and first reprinted in 1921, 5 years later. Issue 20 was first published in October 1917 and first reprinted in 1921. Issue 22 was first published in December 1919. |

There were occasionally minor changes from one printing to the next. The colophons shown next to the painting by Wang Meng in print 01_02 changed twice (see The history of a few paintings). Print 11 of issue 14 went from multicolored to black and white. One painter listed in the table of contents of the 22 issues (see the colophon of issue 15) is missing in our copy of issue 6, two painters in our issue 15 are missing from that table. These discrepancies might also be due to errors in the table rather than changes.

One may speculate on the number of copies of each issue that were distributed, assuming that each printing produced between 500 and 1000 copies (which is the lifetime of a collotype according to the publisher8) : perhaps 2000 for the less popular ones, and 6000 to 8000 for the most successful ones.

The cost of the publication was 1.5 yuan. This is comparable to other cultural products of the time, as a tour of the Fine Arts Museum inside the Forbidden City cost 2.3 yuan in 1916. However, only the upper and middle class could afford such items, as a manual laborer earned 7 yuan a month9. The current market value of these publications is about 50 euros per issue.

2. The Yousheng Book Company

The Yousheng Book Company published many other books documenting and illustrating traditional Chinese paintings, some of which are listed in the colophons. The editorial policy of the Company was to preserve the artistic heritage of China, and to enhance the international prestige of the young Republic of China. At the time there were no art museums in China, actually no museums at all, and many art works left the country in the hands of wealthy foreign collectors. The French Sinologist Paul Pelliot (1878-1945) went to China in 1908 and acquired some ten thousand manuscripts, papers and works of art, which are now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Musée Guimet in Paris6.

The founder and manager of the Yousheng Book Company was Di Baoxian (狄葆賢, 1872-1941). He explains in a book published in 1922 how his project arose : "I set forth in my mind to plan to take hold of famous artistic traces within the nation, searched them out and arranged them and photolithographically published them. It was nearly a matter of taking hidden treasures and making them public for the people of the nation. At that time I was publishing the Shibao newspaper, and once promulgated this doctrine in it. Not long after there came the plan for the Youzheng Book Publishers, where for thirty years we photographically published more than a thousand kinds of steles, rubbings, calligraphies, and paintings. For the most part they were the powerful remnants of that era. This also is a kind of fulfillment of one’s heart’s desire within an age"1. Many of the artworks reproduced in Famous Chinese Paintings were from his own collection, but also from members of his social circle. The latter included high officials, like Fan Zengxiang (1846-1931) and Duanfang (1861-1911), and wealthy merchants. The most prolific collector was Pang Laichen8, also known as Pang Yuanji (龐元濟 1864-1949), a painter in the literati mode, businessman and patron of artists; his widow was forced to sell his collection to the Shanghai museum in the 1950s11. The caption of 12_20 mentions that the first two fans are the property of Mr. Yuan Juexian (袁珏先生先) and that the third one belongs to Mr. Tao Zhai (陶齋先生).

Di Baoxian was a publisher, political reformer and artist. In 1904 he founded one of the most successful newspapers in Shanghai, Shibao (The Eastern Times)3. He was both a commercial publisher concerned with profit, and a cultural entrepreneur closely attuned to current social trends. He responded to one of the most prominent late Qing developments, the drive for women's education, by establishing Funu Shibao (Women's Eastern Times) as a supplement to Shibao4. This might explain why one issue of Famous Chinese Paintings is entirely dedicated to women's paintings. Not surprisingly, that issue (#15) is reviewed in Funu Shibao (issue 18, pp.6-19, 1916). He was also a philosopher : in 1912, he founded Foxue congbao, one of the first Buddhist magazines to be established10 .

The editor of Famous Chinese Paintings, Zhang Jian (張謇, 1853-1926), was not the average publisher either. He was an entrepreneur, politician and educationist, who made significant contributions to the industrialization and education of modern China5.

In 1925-1926, the editor of the publication was the art historian Huang Binhong (1865-1955), who was also head of the art department of Shibao, and a contributor to the edition of Shenzhou guoguang ji6.

|

|

3. Art publishing in China in the early 20th century

A rival bimonthly periodical, Shenzhou guoguang ji (variously translated as "the National Glories of Cathay", "Collected National Glories of the Divine Land" or "Chinese national glory"), also started publication in Shanghai in 1908. Its stated aim was to promote national culture, advocate art, and bring artworks long sequestered in private collections to the attention of the public for their appreciation. It was intended for connoisseurs, scholars and those with an interest in history and cultural heritage, but was also a trade publication for buyers and collectors. It was modelled on the Japanese periodical Kokka6.

Famous Chinese Paintings and Shenzhou guoguang ji were among many initiatives that made the art world in China move from private elite collecting and connoisseurship to a more structured environment, more open to the public, with art exhibits, museums (the first one in 1925), national institutions such as the Ministry of Education creating art classes7, associations such as that "for the preservation of the national essence", the "Zhen Society" and the "Cathay art union". It is this last association that published Shenzhou guoguang ji.

Bibliography

1. Richard Vinograd, Art Publishing, Cultural Politics, and Canon Construction in the Career of Di Baoxian, in Joshua A. Fogel (ed.), The role of Japan in modern Chinese art, escholarship, 2013, pp.245-272.

(http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0w56p2zj)↩

2. Yanfei Yin, Communist or confucian? The traditionalist painter Lu Yanshao (1909 - 1993) in the 1950s, Master's thesis, The Ohio State University, 2012

(https://etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/osu1338318301/inline) ↩

3. Chia-Ling Yang, Power, identity and antiquarian approaches in modern Chinese art, Journal of Art Historiography Number 10, June 2014

(https://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/yang.pdf)↩

4. Joan Judge, Everydayness as a Critical Category of Gender Analysis: The Case of Funu shibao (The Women's Eastern Times), conference on Xin wenhuashi yu Shanghai yanjiu, (Cultural Studies of Shanghai: New Approaches to Its History), Fudan University, Shanghai, December 9 -12, 2011.

(http://www.mh.sinica.edu.tw/MHDocument/PublicationDetail/PublicationDetail_1488.pdf)↩

5. Chang Chien (Zhang Jian) http://www.thechinastory.org/ritp/chang-chien-zhang-jian-%E5%BC%B5%E8%AC%87/↩

6. Claire Roberts, The Dark Side of the Mountain: Huang Binhong (1865-1955) and artistic continuity in twentieth century China, PhD dissertation, the Australian National University, 2005↩

7. Mayching Kao, Reforms in Education and the Beginning of the Western-Style Painting Movement in China, in Andrews and Chen a century in crisis, Guggenheim Museum, 2011, pp. 153–54

(https://ia800500.us.archive.org/20/items/centuryincrisism00andr/centuryincrisism00andr_bw.pdf)↩

8. Yu-jen Liu, Publishing Chinese Art, Issues of Cultural Reproduction in China, 1905-1918 , Thesis, Trinity College, Oxford, 2010.↩

9. Cheng-hua Wang, New Printing Technology and Heritage Preservation, Collotype Reproduction of Antiquities in Modern China, circa 1908-1917, in Joshua A. Fogel (ed.), The role of Japan in modern Chinese art, escholarship, 2013, pp.245-272.

(http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0w56p2zj)↩

10. Francesca Tarocco, The Cultural Practices of Modern Chinese Buddhism: Attuning the Dharma, ed. Routledge, 2007, p.78.↩

11. James Cahill, Collecting Paintings in China, Arts Magazine, 1963↩